Table of Contents

Message from the Chair

Fall 2021 Meeting Summary

Committee News

— EDIJ Committee

— Nominating Committee

— Technical Services Committee

Noteworthy News

— Orwig Music Library

— NEMLA Oral History: Pam Juengling

NEMLA Officers

Publication Information

**************************************************

Message from the Chair

Dear NEMLA members,

I am delighted to share the wonderful news that Brendan Higgins will serve in the role of Member-at-Large until the elections in the spring and Susan Skoog is serving as NEMLA’s videographer.

A wonderful fall began with our first ever joint online meeting! It was a great opportunity for us to learn from the members of the Atlantic and Texas Chapters. We all had the unique privilege of a day of sharing with our colleagues in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, the District of Columbia and Texas. There was so much commonality that I had to remind myself of all of the places we zoomed in from! I do hope this kind of collaboration will arise again. A special thank you to Vice Chair/Chair Elect, Memory Apata, for her leadership engaging members in organizing the meeting. Topics ranged from DEI, Digital Scholarship, Access and Discovery to Special Collections. The Listening Party has become a welcome activity to end the meeting

The work of the chapter is off to a good start. I will mention three specific things in this brief report. As I stated in the spring newsletter, the NEMLA board has agreed to keep the NEMLA archives at the Boston Public Library. There is still a bit of paperwork to complete and an agreement to sign, but we are on the road to successfully depositing our archive. The EDIJ committee had its inaugural meeting in November. I encourage members to reach out to Patrick Quinn to engage further. I am confident this important EDIJ work will be life changing. I am hopeful that an Oral History committee could get re-invigorated this year. Please reach out directly to me if you are interested!

My best wishes for a safe and peaceful holiday season,

Sandi-Jo Malmon

NEMLA Chair

_____________________________________

Fall 2021 Meeting Summary – October 8, 2021

The meeting started off with an introduction from the various chapter heads. As host, Memory Apata provided the initial greetings and provided technical information. She then passed it to Rahni Kennedy from the Texas chapter, who provided a bit of the story behind the joint meeting. It was an idea that he had proposed, which NEMLA’s Lisa Wollenberg supported and began the collaboration. Next to speak was the Atlantic chapter’s Winston Barham, who provided the land acknowledgement, including the lands from each of the represented chapters. Finally, Sandi-Jo Malmon provided some information about the day’s program and reminded folks to stick around for the ever-engaging listening party at the end of the meeting.

The Music Encoding Initiative: Projects for Discoverability, Access, and Performance, presented by Maristella Feustle, University of North Texas, and Anna Kijas, Tufts University

The first presentation of the day was a perfect reflection of the joint aspect of the meeting, for it featured NEMLA’s Anna Kijas and the Texas chapter’s Maristella Feustle. They provided a brief primer on music encoding and the applications of encoding music in XML format, including two examples of recent projects. Maristella described a UNT project encoding a set of rare scores in their Jean-Baptiste Lully Collection. She illustrated how the data was easily used to develop a portion of the rare opera into an arrangement for guitar ensemble, which was subsequently recorded, thus bringing life to the lesser known Lully work. Anna spoke about the Rebalancing the Canon project centered around creating incipits for composers of diverse identities. The project initially considered encoding entire works, but her team decided to focus on creating incipits first, which allowed them to avoid copyright limitations. Both acknowledged that the pandemic had initially disrupted the momentum of the projects, but they quickly became ideal remote projects for their staff and, especially, their student library assistants.

Moving Beyond World Music: An Exploration of Non-Western Music Cataloging Practices in Higher Education and Where to Go from Here, presented by Alastair Canavan, Alexandria Public Library

Coming from the fact that materials from the Western classical music tradition largely dominate performing arts library catalogs, Alastair explored how librarians choose to classify and describe works outside of that tradition. Through study and exploration of several library catalogs, he notes that there are discoverability issues for non-Western music, both in the metadata provided by catalogers and from the limitations of OPACs or discovery search systems. Some catalogers have previously relied on the generic subject term “world music” when little was known about the style or it was difficult to determine region. Moreover, some search engines do not allow for limitations by language or genre form headings, which would greatly improve discoverability of these types of materials. Alastair suggests that catalogers should revisit existing records, when possible, and ensure that subject terms include additional terms, like “popular music,” “folk music,” and geographic information about the music or possibly the creator. The presentation expanded into a lively Q&A discussion, which included topics like the limitations of LC genre/form headings and the ceaseless work that all music librarians must do to ensure our catalogs promote discoverability of all forms of music.

Music in the Margins: Advancing Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Through the Music Library, presented by Tim Sestrick, West Chester University

Building upon the meeting’s theme of diversity and inclusion, Tim explored how librarians are addressing the problem of systemic racism and the exclusion of diverse voices within our libraries. He ruminated on how librarians are both consciously and unconsciously handling these systemic issues and proposed that we take an “activist mentality” by responding to the requests and events that are happening now. One solution is to collaborate with the students, which led him to the Music in the Margins project, a collaboration with music library interns.Their work began as a blog which highlighted marginalized composers and musicians, then led to a panel discussion with faculty concerning the Euro-centric and male-dominated canon. This work led to discussions with the School of Music about programming works from diverse voices in their ensembles.

Lightning Talks

The Directory of Digital Scholarship in Music: reconciling usefulness and sustainability in an online directory, presented by Francesca Gianetti, Rutgers University

In the first of three lightning presentations, Francesca Gianetti discussed the work that has gone into creating the Directory of Digital Scholarship in Music. The directory provides a snapshot of how Digital Humanities projects can look in the music field, whose scholarship often still deals with print scores and recorded sound that can be challenging to present in a digital medium. In addition, she acknowledges that such projects – and even the directory itself – require time, funding, and other resources, which can affect a project’s scope and usefulness.

Increasing Music Accessibility for Patrons with Print Disabilities, presented by Blaine Brubaker, Kristin Wolski, and Sabino Fernandez, University of North Texas

The next presentation was pre-recorded by Blaine Brubaker, Kristin Wolski, and Sabino Fernandez at UNT and discussed a host of valuable software and other technologies to aid music students with visual disabilities. They highlight the application of MusicXML to create Braille scores and various software options for blind or low vision musicians, such as music readers, screen readers, and composition tools. They encourage all music libraries to install such software on their patron workstations and work with their institutions’ accessibility services office to promote these specialized library services.

We Cosset Our Special Collections: But Who Cares?, presented by Donna Arnold, University of North Texas

The last presentation of the lightning talks came from Donna Arnold at UNT, who provided an overview of the special collections housed in their library. The scope of these materials is large: piano rolls, Schoenberg correspondence and music manuscripts, Duke Ellington and Stan Kenton collections, Dallas Opera memorabilia. Despite the richness of the collection, the presenter lamented the minimal attention the materials have received among scholars and the local community. Yet there have been valuable collaborations with faculty to have the materials part of the music research curriculum. These outreach efforts should be at the forefront of any libraries with special collections, for they can sustain and grow a collection.

Value added: Music teaching and Scholarship with MIT special collections, presented by Jonathan Paul, MIT

Staying within the world of special collections, Jonathan Paul presented on the application of archives and special collections materials for research and teaching. Two collections that he highlights are the robust Herb Pomeroy Jazz collection and MIT music library’s Oral History collection, which is beautifully indexed and fully searchable. The Herb Pomeroy collection contains scores, parts, and audio recordings from the teacher/trumpeter/band leader, as well as notebooks from his time studying with Joseph Schilinger and his music teaching materials. His legacy makes the collection valuable for students and scholars studying jazz pedagogy and history, yet Jonathan remarks that intriguing comparisons could be made between this and other local collections, such as those at Berklee College of Music and Harvard University. These suggestions led to a discussion among the attendees about how collaborations between local special collections might encourage deeper scholarship from researchers and excellent outreach opportunities.

Maybe You Should Talk to a Music Librarian: Introductory Thoughts From Librarians Supporting Music Therapy Programs, presented by Karen Berry, Radford University, Jessica Abbazio, University of Minnesota, and Brendan Higgins, Berklee College of Music

The final presentation for the day was another cross-chapter presentation, delivered by Karen Berry, Brendan Higgins, and Jessica Abbazio, from ATMLA, NEMLA, and MLA Midwest chapters, respectively. Their presentation evolved out of discussions around their role as music librarians who assist the music therapy departments at their institutions. That field can be a mix of music and health sciences, which means that it requires different research skills and involves databases and literature outside the normal music collection. After describing some of their individual challenges at their institutions, they elaborated on the various problems and anxiety that music librarians might encounter in this role and offered solutions based on their experiences. Recognizing that other music librarians might benefit from further discussions, they proposed that an MLA Interest Group might be of value to the greater community.

Chapter meetings

Following the day’s presentations, the individual chapters met in breakout rooms for chapter meetings. Since NEMLA holds their business meeting at the Spring meeting, the time was spent providing NEMLA updates. Sandi-Jo led the discussion with updates about the board and special officers: Patrick Quinn was chosen as our first officer for Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Justice, Brendan Higgins elected to temporarily take over the role of Member-at-Large after Allison Estelle opted to step down, and Susan Skoog is serving as NEMLA’s new videographer. In other news, Emily Levine is in discussions to have the NEMLA archives maintain their custodial home at the BPL. Sandi-Jo wants to revive the Oral History project, not only to capture the insights from some of our retiring members, but possibly document the thoughts of some members that are early in their career. Finally, Memory opened up a discussion about the Spring meeting and whether it should be held online or in-person.

The meeting concluded with another enjoyable Listening Party, hosted by Peter Laurence, Harvard University.

Submitted by Brendan Higgins

Listening Party Playlist

- Roebuck “Pops” Staples – Black Boy

- The Clash – Know Your Rights

- Lakshmi Shankar recital at The City College of New York — October 17, 1968.

- New York Disco Orchestra – Reverie (Debussy)

- Great Leap / Nobuko Miyamoto – “Mottainai – don’t waste what Nature gives you…”

- Solange feat. The-Dream and BJ The Chicago Kid – F.U.B.U.

- Sinead O´Connor – Live at Madison Square Garden

- Undine Smith Moore – Before I’d Be a Slave

- Gil Scott-Heron – The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (Official Version)

Submitted by Peter Laurence

_________________________________

Committee News

EDIJ Committee

The EDIJ committee had their first meeting at the beginning of November and discussed several topics to help define the scope and future projects for the committee to undertake. Notable discussion points include:

- A follow-up survey to the Summer 2020 EDIJ survey

- This would help us track continued support for EDIJ initiatives in members’ institutions and in NEMLA and how that has or has not manifested into institutional action. We can use this to then provide recommendations to members on how to move forward in the current climate.

- Crowdsourcing an EDIJ glossary of common terms

- This could be a valuable resource for the music library community to understand the most relevant definition of words that are often used in EDIJ discussions. With greater common language understanding, we can help define our organizational goals and institutional recommendations with clear, concise, and understandable language.

- Creating or providing educational materials on EDIJ topics to our members

- We may be able to collect relevant national MLA resources, resources provided by grant funding, or freely available resources in one place for members and member institutions to reference more quickly and easily.

- Understanding and increasing the impact of land acknowledgement statements

- We can aim to provide clear recommendations for members and institutions on how to create effective land acknowledgement statements that can point to resources about the occupied land. By understanding more about how institutions create these statements, we can also provide resources or recommendations on how to leverage them effectively so that the statements have some greater impact.

The committee is looking forward to the challenging work ahead and will be meeting again soon. Keep an eye out for our next meeting announcement and feel free to join! The EDIJ committee also still has plenty of room, so if you are interested in joining the work of the committee, please don’t hesitate to reach out to the current chair, Patrick Quinn at pquinn6 at bu.edu. If you have comments, questions, or suggestions about our work, please feel free to reach out to any of our members.

Patrick Quinn (Chair, 2021-2023), pquinn6 at bu.edu

Yamil Suarez (2021-2023), ysuarez at berklee.edu

Jennifer Hadley (2021-2023), jthom at wesleyan.edu

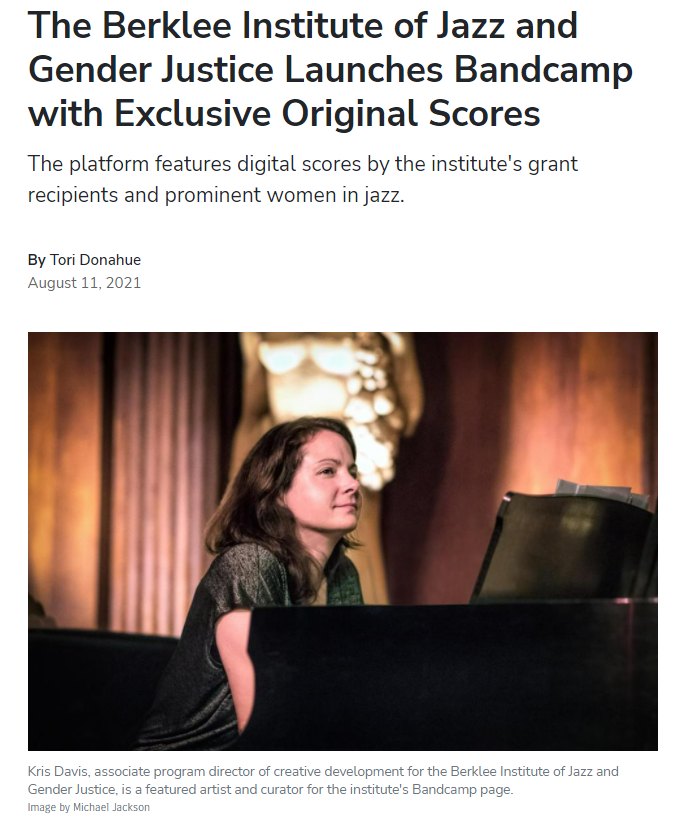

The first local resource we’ll spotlight is from The Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice:

“The Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice has launched a Bandcamp page highlighting the pioneering compositions of women in the field, including those at Berklee. The page includes original scores from the 10 women who were awarded the first-ever Score Compilation Grant, which allowed recipients to create digital collections of their scores in the Berklee Library. The inaugural recipients of the grant were Melissa Aldana B.M. ’09, Courtney Bryan, Marilyn Crispell, Ingrid Laubrock, Nicole Mitchell, Tineke Postma, Michele Rosewoman, Shamie Royston, Angelica Sanchez, and Helen Sung—all of whom are highlighted on the Bandcamp page.”

___________________________________

Nominating Committee: Seeking volunteers for open positions

We are now accepting nominations for the following officer positions on the NEMLA Board:

Vice-Chair/Chair-Elect

- Performs the duties of the Chair in the latter’s absence.

- Serves as Chair of the Program Committee.

- Serves as an ex-officio member of the Education & Outreach Committee.

- The term of office shall be one year, after which the Vice-Chair shall succeed to the office of Chair and then Past-Chair, meaning a commitment of three years.

Member at Large

- Acts as liaison to relevant professional organizations in New England (such as the New England Library Association (NELA), the six state library associations, the New England chapter of ACRL (ACRL/NEC), and the New England chapter of the American Musicological Society) primarily to promote information exchange and outreach.

- Serves as Chair of the Education & Outreach Committee.

- Writes summaries of the biannual NEMLA meetings to be published in NEMLA newsletters.

- The term of office shall be two years.

Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Justice (EDIJ) Officer

- Serves as Chair of the EDIJ Committee.

- Leads the chapter’s EDIJ efforts to identify and dismantle barriers to equity, diversity, inclusivity, and justice within NEMLA and related organizations.

- The term of office shall be two years.

Web Editor (non-elected position)

- Maintains the NEMLA website, listserv, and Board listserv.

- Serves as an ex-officio member of the Board.

- Serves as a member of the Publications Committee.

- The term of office shall be two years.

Terms of office begin immediately after the spring meeting. Members must be in good standing and current with their dues. The Vice-Chair/Chair-Elect must also be a member of the national Music Library Association. Nominations are welcome through January 31, 2022.

If you would like to nominate yourself or a fellow NEMLA member for one of these positions, or if you have any questions, please contact one of the Nominating Committee members:

Lisa Wollenberg, Nominating Committee Chair, Lwollenbe at hartford.edu

Sharon Saunders, ssaunder at bates.edu

Anne Rhodes, anne.rhodes at yale.edu

Anna Kijas, anna.kijas at tufts.edu

Thank you for your consideration!

Submitted by Lisa Wollenberg

______________________________

Technical Services Committee

Cataloging Pandemic Performances: Zoom ahead with these tips!

In the past year and a half, many of the schools where we work have been presenting their concerts, recitals, lectures, and other events as streamed videos on Zoom, YouTube, or other online services. Several members of NEMLA’s Technical Services committee, in particular members from Berklee College of Music (Kristen Heider), Wesleyan University (Rebecca McCallum), and the New England Conservatory of Music (Hannah Spence), have been grappling with catalog records for these streamed events.

In general, the document OLAC Best Practices for Cataloging Streaming Media Using RDA and MARC21, Version 1.1, April 2018 is still the standard to follow, and will hopefully provide answers to any thorny questions you have. For the most part, there is actually nothing radically different between cataloging a Zoom- or YouTube-streamed event and cataloging any other streaming media file. A few of the differences we have noticed, though, include:

- Varying sources of information about the event:

Since many concerts were not open to live audiences, there were no printed programs, and finding adequate sources of information about the event often requires some online detective work - Varying file types and technical specifications:

Audio- or video-capture methods may have been different than what was established in a school’s performance space pre-pandemic. Therefore, file types or digital specifications may be different than expected. (If you’re not sure what the technical specifications for a file are, you can use the free online tool MediaInfoOnline to determine those specifications.) - Multiple locations for one event:

If a concert was performed and recorded in a particular space on campus, the 518 field (date/time and place of an event note) will look much like 518 fields from before the pandemic. However, if the video includes speakers or performers who are joining a video-call from remote locations, you may not have one specific location to list. One solution is to simply enter “various locations via Zoom” or a similar note.

For those catalogers who are not used to working with streaming media materials, here is an overview of the fields often included in catalog records for online audiovisual files.

Fixed fields:

| 006 | The 006 field is a place to code characteristics that don’t fit into the usual LDR or 008 fields. For online audio and video content, the 006 helps indicate that the item is a computer file (006 pos 0=m), that it is online (006 pos 6=o), and that it contains sound (006 pos 9=h). |

| 007 | Originally, 007 fields were designed to code physical characteristics of resources, but they can expand to include some technical aspects of non-physical resources too. One benefit of 007 fields is that you can include multiple instances of an 007 field, to code for different aspects of a resource. Most online audiovisual material will include an 007 for its electronic nature, and another 007 for either its audio nature or its video nature. |

Note: As is true for physical materials, the fixed field coding should distinguish between musical audio files and nonmusical audio files (such as lectures, panel discussions, clinics, etc.)

3XX fields:

3XX fields generally describe the physical or technical specifications of a resource. In addition to the standard 336, 337, and 338 fields you will see in most RDA records, there are a few other 3XX fields commonly in use for audiovisual materials:

| 344 | Sound characteristics (for streaming audio) |

| 347 | Digital file characteristics |

| 380 | Form of work (mostly used for streaming video) |

Note: There is also a field 346 for Video characteristics, but this field tends to be used most often for physical video recordings, not computer-based video files

5XX fields:

| 518 | Date/time and place of an event note (already in common use for physical audiovisual materials). It can be a freeform note or can be divided into specific subfields $d (date), $o (other information), and $p (place). Most of our recordings have been recorded in one particular place, but some events we are cataloging were captured on a platform such as Zoom, with performers joining from multiple locations. One solution is to define the location as “various locations via Zoom.” |

| 516 | Type of computer file or data note |

| 506 | Restrictions on access note |

| 588 | Source of description note |

Here are some examples of the previously discussed fields you will see in records for streaming online audiovisual resources. Technical specifications, uncontrolled note field wording, and 856 subfield $z wording may vary from one institution to the next.

For streaming audio (musical) recordings

006 m|||||o||h

007 sr|nsnnnnnnnnd

007 cr#nnannnaanun

300 1 online resource (streaming audio files)

336 performed music $b prm $2 rdacontent

337 computer $b c $2 rdamedia

338 online resource $b cr $2 rdacarrier

344 digital $g stereo $2 rda

347 audio file $b MP3 $f 96 kHz $w rda

518 (info about where recorded, when streamed, etc) OR various locations via Zoom

516 Streaming audio

588 The concert program pdf and audio files

506 Available to [institution name] users only

655 Live sound recordings $2 lcgft

856 40 $z Click to access streaming audio (Authorized [institution name] users only) $u [URL for the audio file]

856 42 $z Click to access program notes $u [URL for the program]

For streaming video files

006 m|||||o||h

007 vz#czazzu

007 cr#cnannnmuuuu

300 1 online resource (streaming video files)

336 two-dimensional moving image $b tdi $2 rdacontent

336 performed music $b prm $2 rdacontent

337 computer $b c $2 rdamedia

337 video $b v $2 rdacarrier

338 online resource $b cr $2 rdacarrier

347 video file $2 rdaft

380 Filmed performances $2 lcgft

518 (info about where recorded, when streamed, etc) OR various locations via Zoom

516 Streaming video

588 The concert program pdf and video files

506 Available to [institution name] users only

655 Concert films $2 lcgft

856 40 $z Click to access streaming video (Authorized [institution name] users only) $u [URL for the video file]

856 42 $z Click to access program notes $u [URL for the program]

Finally, if you’d like to view a few full record examples, here are some OCLC numbers you can search for:

- From the Eastman School of Music: OCLC #1250320812

(streaming audio, musical performance) - From Indiana University: OCLC #1244757236

(streaming video, musical performance) - From the New England Conservatory of Music: OCLC #1259362857

(streaming audio, musical performance) - From Berklee College of Music: OCLC #1261763480

(streaming video, interview)

Submitted by Rebecca McCallum

********************************

Noteworthy News

Orwig Music Library updates

The Orwig Music Library at Brown University has reopened, following a major renovation in Summer 2021. Although the stacks layout is basically the same as before, we (the staff) are enjoying the new HVAC (including functional thermostats) and upgraded life safety systems, in addition to a touch of new paint and carpet. We also wish Senior Library Specialist Sheila Hogg a happy and peaceful retirement after 45 years of service to Brown. Peter Riedel is our newly hired Senior Library Specialist. Welcome, Peter!

Submitted by Laura Stokes

____________________________

NEMLA Oral History – Interview with Pam Juengling

Pam Juengling retired from the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2017 after spending 35 years there as a music librarian. She started her library career as an undergraduate student worker at Minnesota State University, Mankato while studying organ performance, music education and German. Encouraged by her supervisor Kiyo Suyematsu, she went on to earn her MLS from SUNY Geneseo, studying music librarianship under Ruth Watanabe at Sibley Library, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester. As a library student, she attended the first of many MLA meetings in Boston in 1978. After graduating, Juengling became a music librarian at the recently founded Northern Kentucky University. She moved on to UMass in 1982. Juengling joined the Midwest chapter of MLA while in Kentucky then NEMLA with her move to Massachusetts, serving on committees in both chapters. She served twice on the NEMLA board, as member-at-large and secretary/treasurer, and hosted a meeting. She was a member of MOUG from its inception and served as its secretary/treasurer, served on the Naxos Music Library Board and the EBSCO Music Advisory Group. She contributed several chapters to the 2nd edition of A Basic Music Library, published by ALA in 1983.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

MARCI COHEN: It is Tuesday, January 9th 2018. I am in the Hadley, Massachusetts home of Pam Juengling. She has recently retired from University of Massachusetts, and I am interviewing her today for the NEMLA and MLA oral history. I see that you graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato. Is that where you grew up?

PAM JUENGLING: I grew up in a suburb of Minneapolis, which was about 90 miles northeast of Mankato. I looked at a variety of schools, and the University of Minnesota was the obvious one, right in town. I was looking particularly at organ performance, focused on the applied teacher. University of Minnesota was just too close to home. I visited several colleges, as kids do. I didn’t really know much about Mankato, but it just clicked. So, I went to Mankato and studied organ performance and German. Somewhere along the way my dad said, “Now what are you going do with these degrees in organ performance and German?” I hadn’t really thought about that. So I said that I will add the teaching component, and I’ll teach. I did pick up the education block and was certified to teach K through 12 music, both choral and instrumental, and 7-12 German. And I absolutely hated student teaching. I just hated it. If it had been just pure music and teaching I think it would have been fine. I wasn’t ready for all the discipline and lack of attention and bureaucracy, and it just really made for a bad experience. But at the same time I had seen a sign in the window of the music library. I was in the performing arts building and in the music library a lot. And the sign read, “Student help wanted.” “Why not? You could always use a few bucks.” I’m in the building all the time anyway, I knew Miss Suyematsu, too, who became my good friend Kiyo. I thought she would be fine to work for, so I stopped in and was hired.

And Kiyo took a real interest me in me because I was interested in what was going on in the music library. It developed into more than just a student position. I had more responsibility, and she took interest in many of her students who were technically inclined. This was when we still had card catalogs, reel-to-reel tapes, LPs. So anyone interested in having an ability in languages, technology, good solid background in music who could take on more – and I was one of those lucky people. I had more responsibility there, and she asked if I was interested in helping the music catalogers search for copy. And I said, “Music cataloger? Copy? I don’t even know what you are talking about.” This was the mysterious place where materials came from, ready to go. OCLC was pretty new at that time.

I would have been at Mankato from ‘73 to ‘77. I searched NUC copy back in the old days of printed books, many, many of them, from the National Union Catalog. And the subset of music. I also got to start searching OCLC copy, and if I thought I had a match my job was to print it off, insert the printout in the item and set it aside for the cataloger. Which seemed like a pretty big deal for me at the time, and now of course thousands of people do that thousands of times a day! But I thought this was very cool. Nancy [Olson], who was the music cataloger and the non-print cataloger, went on to found the OLAC group [Online Audiovisual Catalogers]. She was a mover and shaker in her field. I was really lucky to work with her as well as with Kiyo.

Both of these women took an interest in me, trained me, directed me, and as graduation approached it was especially Kiyo who said that there are extension courses that the University of Minnesota offered at Mankato. Would you be interested in taking them? And I said that I don’t even know what library science is and what you do. I mean you boss us around, you supervise us, I don’t really know what you do. So I learned what a librarian does, especially in a special discipline in music librarianship. So I took a few courses and it was just fine.

Kiyo said, “I think when you graduate you should look at a graduate program in library science. Make sure there’s a special program in music, because you don’t want just the generalist training, you want music, and here’s the one I think you should go to, SUNY Geneseo in collaboration with the Eastman school.” Which of course I had heard of, and Ruth Watanabe.

I did end up going to Geneseo. I had an assistantship there working for the children’s literature faculty member. I thought, “Kiddie lit?” but the professor was excellent in her field. Margaret Poarch, no longer living. She served on Caldecott Award Committees and other award committees, consultation committees, curriculum committees, and was an important reviewer. Anyway, she taught bibliography classes, literature classes, and I was typing up lists and lists and lists and gathering up books and just being a general assistant. Not doing any teaching because it wasn’t my field. But I learned a lot about how somebody who is really outstanding in her field handles correspondence and prepares for classes, and this was all very interesting. She was absolutely a delight, eloquent and funny – she was from the south, had a charming accent, and treated me so nicely. It was just such a nice package. And then we remained friends after I worked for her and graduated.

I had some good people who were helping me and took an interest in me, my interests and my skills. So that’s the background of how I started out in Minneapolis to Mankato to Geneseo, NY. The experience at the Sibley Library in the Eastman School was invaluable, of course.

When I went to Rochester the first time just to go check it out, I went to Eastman – the old Sibley Library – found a door, walked in, found a place where I could ask for help and said, “I’m trying to find the library,” and this nice woman was standing nearby. “Oh, are you looking for the Sibley Library? I’m going that way, you can follow along with me.” Well, it turned out to be Ruth Watanabe! And of course I knew the name but didn’t know what she looked like, but she was a big factor in choosing to go to this program. The music librarianship program was offered jointly through the SUNY Geneseo Library School and the Eastman School. There were summer seminars and also some internships. There were only five or six of us who were in that class. We had some classes at Geneseo taught by the one of the music historians in the music department, John Kucaba, who loved what he was teaching. He’d been doing this a long time, and he’d seen a lot of music librarian students come and go. It was a trip through music bibliography, day one to the present.

When my program was ending and we all started looking into jobs, I applied for a whole bunch of positions and had two interviews. One was at Northern Kentucky University, and I thought, “Kentucky, I’ve never been there.” I thought it was the South. I thought it was probably not the most progressive place, probably an old, run down campus. But I learned this was a new regional campus – there was already an Eastern Kentucky University and Western Kentucky University but there’d never been a campus in the North, so this university was founded in maybe 1968, 1970. Brand new campus, sparkling architecture, beautifully kept, everything hung together, well planned. I went there in 1978, and there was money to develop the campus, to build library collections, to hire people. And there really wasn’t any music person in the library at all, so even though the job I interviewed for was music and non-print cataloger, they really needed someone with a music background who could also do reference and instruction – library instruction was developing at the time. Small music faculty, but good people, and the Fine Arts building was right next door to the library which was really convenient. It was in suburban Cincinnati – I was six miles from downtown Cincinnati, so I didn’t really feel like I was living in Kentucky — in the hills of Kentucky, in the rural South — this was suburbia. Right across the river was Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, part of the University of Cincinnati, an outstanding music institution, lots of arts organizations, the Cincinnati Symphony, Cincinnati Opera, and a good chamber orchestra.

I learned a lot and I was given a lot of responsibility. That’s the advantage in a small place that’s still growing — if you think you can do it, do it. And serving on committees, learning how the academic scene works — and doesn’t work — that’s valuable to learn, too.

But after about three years, I felt I had learned about what I was going to learn there, and the size of the music program, and it was really hot summers for a Northerner, and right in the Ohio River Valley, humid besides. And I thought, “If I change jobs, then I can find something in the North, that would be great.” I think it was through the MLA placement service, or just the newsletter that listed jobs. One day I saw the Massachusetts listing, University of Massachusetts. And in the mail came a little piece torn out of the New York Times, about the same job listing at UMass Amherst, from Margaret Poarch, the children’s librarian whiz I had worked under: “Thought of you.” We were still touch, and she knew how I was doing, and some things were good and some things not so much, and that I probably belonged in the North, and ready for a bigger experience.

So within a few days, I felt that job was comin’ at me. Well, I need to apply, and I thought, “Oh, University of Massachusetts.” I didn’t even know which school this was actually. I was confusing it with Amherst College, which to this day people confuse. Hardly the same, but — and schools in Boston, and I really wasn’t sure — Amherst, Amherst, and Belle of Amherst, oh that Amherst, and Emily Dickinson. Then it was easier to look up, get information about what the place might be and I thought, “It’s probably more similar to the University of Minnesota. Big land grant school, big music department. This is the big time. I don’t know if my experience in Kentucky, three years going on four, is gonna be enough.”

The music library was in the Fine Arts Center, which is a good thing. It was immediately adjacent to the music department. There was a good collection. It was a big music library, lots of audio visual equipment. There were some staff, student help. Heard and read good things about the faculty, and I could see from the main library, this is the big time. I wondered if I could even cut it. But they wanna interview me, I’ll do it.

Went through my paces with the interview. And at lunch, finally got to meet a member of the music faculty. But then I felt like I really found a soul mate. A real musician. And they desperately needed a music librarian, and he had seen my resume so [he] knew I had had appropriate training, and I was getting involved in professional groups, and this thing called OCLC, I was in and I was using it, and that was just the wave of the future. And he became an advocate right away. It was John Jenkins.

MC: Did you envision when you started there that you were going to be spending the rest of your career?

PJ: I had no idea that I’d turn out to be a lifer. I figured I’d been four years in Kentucky, so probably another four or five years here, and then we’ll see what the next adventure is. But by then you know you’re getting a little bit older and — so I was 27 when I came. So into your early 30s, and you start making a life for yourself. The friends you develop became more substantial friends. And the activities I was in, my life became here, not just my job.

The going did get tough in the early ‘90s. Budgets were cut. The administration, the state administration was such that they were not looking so favorably on higher ed, public higher education. When you have BU, when you have Harvard, why do we need to fund public higher education? That continues to be an issue now. And I’d say, well, not everybody gets into Harvard. Not everybody can afford MIT. And so many of our legislators are products of the excellent private schools in Massachusetts, from one end to the other, from Williams to Boston. So until there was a little more understanding of public higher education and the costs, which of course now is on everyone’s mind, times got really tough. We had a library director that many of us had difficulty with, and I had more than my share. And I thought, “Maybe it is time.” So around 1990 I applied for a job. The only job I’ve applied for since I came to Massachusetts. I was granted an interview, but it sent me to the South and I think the interview was in November. It was 90, 92 degrees and I thought, “What, I should have my head examined? What was I thinking?” So, I didn’t think the interview went all that well, and I don’t think it would’ve been a good fit, but fortunately we could tell right in the interview. I think they thought the same thing. I thought, “This is just not a happy match.” So, that was that.

It was a good learning experience, and decided I have to remember this is my job. It’s my career. It’s my profession. It’s not my life. And when there are difficulties at work, as there always will be, just like sometimes there are difficulties in life, just remember it’s your job, and you get to leave at five o’clock, and then you have a life. And it doesn’t mean you’re any less professional or that you care any less, or that you don’t work just as hard. It becomes one facet of your whole person and your whole life. And it was a real important lesson for me to learn, that I have a problem at work, I don’t have a problem in my life.

And other colleagues, I think, figured that out too. And some of us just backed off a little bit from that 115% commitment that we thought was the right thing to do. Maybe not, maybe 100% is enough. And we have a life, and that’s what sustains you and gets you through difficult times at work, and this too shall pass. And she left, and we got a new director that was just fine. And I thought, “Well, I’m really glad I didn’t bail on what otherwise was a pretty good situation for me. At work and living where I live, and in the area where I live. I’m really glad I stuck it out and learned this important lesson.”

MC: How did your job duties change over the years?

PJ: When I started at UMass, the music library was one of three branch libraries. There were two other science libraries, and a self-contained branch in the Fine Arts Center. There were, variously, three or four staff members, bunches of student assistants. There were 20, 22, sometimes more, students to supervise. So, I supervised the supervisor. There was a fair bit of administrative work, selecting materials.

All of this was when OCLC was underway and way active, but we didn’t yet have an online catalog. We were still filing cards in a card catalog. We got microfiche prints of a union list of serials among the Five Colleges. It was called Pioneer Valley Union List of Serials. Once a month a new fiche would come and we stuck those in a notebook and that’s how you looked up journals and holdings. We had one computer in the library for staff use, because what would the public do with it? And we just took turns looking up this, looking up that, but there wasn’t that much you could really look up, so a lot of it was access to OCLC.

No databases in music at that time. There were mediated searches of some of the big, big conglomerates, but I wasn’t involved in that. There were specialists at the main library who studied that and the search protocols for that. It was very complex. You made an appointment with the database librarian, so that changed.

But one nice [thing] from the very beginning, I was always invited to attend the music department faculty meetings once a month. If I had something to say I was on the agenda, otherwise I sat and listened, and I learned a lot about the curriculum, about the faculty, about the students. They really made me feel a part of the department even though administratively I was part of the library. They were always kind to me, nice to me, treated me professionally, treated me with respect, became friends.

And when I heard from some of my other colleagues that, “How do you possibly get invited to the department meetings?” I don’t know. When I came, “Here’s the key to the mailroom, and all the meetings are on the first Thursday.” How lucky I was! And learned a lot, and really my heart and soul was with the music department. Administratively, I was always with the library, but that was so fortunate, and I hear so many people, “Boy, I wish the chemistry department would invite me,” or, “I asked to come in.” “No, these are closed faculty meetings. You can’t.” So, I didn’t know how good I had it that way.

[A big change] was students coming to do their listening and viewing on 35, 40 listening/viewing stations: LPs, reel-to-reel tapes, cassette tapes. Most of that didn’t circulate. They may not have had the equipment themselves anyway, but they had to come and sit and do their listening. We evolved eventually to CDs. I was aware of the development of this new thing called CDs and learned about it at NEMLA, and just in the professional literature and I thought, this is something we need to keep an eye on, and I think this is gonna catch on. I made my case and said, I think we should buy a few of these machines and start buying a few CDs, and “Well, okay, you’re the music librarian. If you think so.” And it was all part of other technology rearing its head, and we were so lucky that the music library was able to be part of it. So, I was seen as really cutting edge and forward thinking for saying, “Yeah, this CD thing, I think we want to get in on this.”

MC: I saw that you spoke at a 1986 NEMLA meeting. You did a talk on compact discs as a hot topic.

PJ: It was. It was at Smith College, and we each took a little piece of something. Yeah, this was cutting edge stuff. And other people shared at NEMLA as well. I certainly wasn’t the first. But the care and feeding of CDs, and what kind of labels can you put on them, or can you write on? Will the labels come off inside the machine? Will they throw the balance off? We were learning all that. And it was something that was very practical, up my alley. With running a music library, supervising staff, supervising students, we need to know: can you stick a label, can you write on them? And [I] did some investigation and all of a sudden I was certainly not an expert, but someone that NEMLA would say, “Well, could you share that with us?” And it’s just an informal little thing, I said, well sure.

And so I think technology, without a doubt, had the greatest impact on my job, of eliminating card catalogues and moving to an online environment. And the change in the way we listen, to coming in and sitting down with LPs or tapes, to CDs which then became more practical to circulate, and then eventually with streaming. And students are walking across the campus plugged into their phone and doing their listening assignment. How well are they doing? I don’t know. Are they doing other listening that is more substantial and the score is in front of them? I hope so.

Meeting with classes has changed tremendously from bringing a stack of books and telling them, “Now this resource has this, and here’s the call number. You’ll need this,” to “Well, let’s take a look at the latest version of the library website,” and “Where have we hidden whatever you need to find, and what is it called?” And then digging into databases, into electronic resources. That’s just a tremendous change in instruction and what the students need to know and how they do their work, as well as campus and beyond resources — IT departments and writing centers, and all that sort of thing. That kind of support wasn’t available, at least not readily available or known to those of us in the library. So we became much more broad in our services.

MC: How about the balance between cataloging and public services, did that shift at all?

PJ: I did shift. When I came, there had been a music cataloger. Unfortunately she had an illness and had died, and people were mourning her as one would expect. Administration or those in charge of the affected departments were unsure of exactly which way to go. And they just said, “Well, let’s get the music librarian hired. Then we’ll see about the cataloging or what we should do or combine with something.” Turned out that my background, just because my first job happened to be cataloging, music cataloging and non-print, and there was no other music person so I took on the other music librarian duties that I was capable of doing, the cataloging. And I’d worked with OCLC, and I knew how to search and copy, and copy editing, and original cataloging, and gone to workshops that the chapter or OCLC offered, so I could do that.

And I didn’t know any better, so I said, “Oh, sure!” So I was in one building to run the music library and another building for the cataloging department to do music cataloging. And soon found out these are both full time jobs. And when you’re new, you don’t want to complain or make it appear that those old doubts about, “I can’t do this. I’m not cut out for this, I’m not good enough. I don’t have the background for this big institution.” So, just kept trying to do my best, but I ended up behind [in] both places. And finally had to go to one of my assorted bosses. And I also, because I did selection, we had a separate collection development division, and I reported to three associate directors for what was called public services, technical services and collection development. So I went to one boss and said, “I can’t do this. I can’t say nobody can do this, but I can’t do this.” “Well, that’s not a surprise. We had a cataloger before. We should get a cataloger now.” And I thought, thank heavens.

And so we did hire a music cataloger, and she knew what she was doing. She just needed to find out how we do it. So once she was hired, trained, and I told her “Here’s what I know and can share with you,” I was back in the music library and collection development. And we were lucky to have a music cataloguer all the rest of my career. So that was under two years, I think, before I cried wolf and said, “I can’t do this.”

MC: I don’t think it’s considered crying wolf, with what you had to take on. You mentioned that you had a lot of student workers that were coming through. Do you know if any of your students workers went on to become music librarians?

PJ: I do. I remembered some of them because I see them at professional meetings, either New England or national meetings. When I retired I posted a little message on MLA-L and on the New England listerv, NEMLA-L, that I’ll be retiring from UMass. And I’ll have to say, the messages I got back from colleagues. Some were just a brief, but some went into great detail and sent a whole page of, “You may not remember me, but I was a music student at UMass, and I came into your office and said, I just don’t know what I’m gonna do with this music degree,” — I’m thinking of someone in particular — “and I love it but I’ll never make a living at it, and what do you do, and how did you learn how to do this?” That person now is a music librarian at a very distinguished institution and making a name for himself, and professionally active. I got a few like that. And as word spread, not just through the music library world, but the music world, some of the students I worked with wrote “I wouldn’t have gotten my masters if it weren’t for you,” or “I never would’ve passed my comps.” And I hate to say there are so many students and they all kind of blend together, but there are so many students and I don’t remember all of those individual instances. It’s because that’s what we do. That’s what I did, and I took it seriously at the time, and I knew the students and would try to go to their senior or graduate recital. And then it’s over and done and I kind of forgot, and I don’t think that’s heartless, I think it’s just there were so many students. And in 35 years.

And then the students who worked in the music library, too. Some of those were music students, some were not. But they learned about the libraries and thought, “You know, this might not be a bad gig. So how did you do this?” and because UMass didn’t have a library school, many of those students didn’t even know there was something called library science. And you’d go off and get preferably a masters degree, ALA accredited. And that’s how it’s done.

But, especially when I retired, some of the messages I got, and I’d almost forgotten, not necessarily the person, but our exchange, or that I really made a difference with them. And I’ll tell you, dab away a few of the tears — that was so sweet and so thoughtful. Sometimes it happens at thesis or dissertation time, and you read the acknowledgements, “And I thank these people,” “And in the library.” And we kind of expect that, not take it for granted. But it was at retirement when some of those really lovely messages came through. I thought, “Yeah, there is another generation that I helped make a difference,” and that’s not in your job description. That’s just one of the many benefits and perks that comes from working with some good people.

MC: Going along with that, I wanted to talk about your involvement with MLA. You mentioned that Kiyo really mentored you at your first MLA meeting that was in Boston in ‘78. You want to talk about how you got involved in MLA?

PJ: Kiyo Suyematsu was the music librarian at Mankato who was so helpful to me, took an interest in me, and I don’t even know if I knew the word “mentor” at the time. But that’s exactly what she did and what she was. And when I was in library school we heard about the importance of professional organizations, ALA, and for us, the little group of music library students, MLA. And their meeting was coming up in February of ‘78. Yes, the blizzard of ‘78 meeting in Boston. And I was in Rochester, Geneseo. That’s not that far away. And the library school had some professional development grant money for students. And of course I hardly knew what professional grant money even meant at that time. But you could apply for a meeting, and I thought, well why not? People are telling me you should get involved or go to MLA, and it’s not very far away. I talked to [Kiyo] about it and she said. “Oh yes, we’ll room together, I’ll show you around. Oh, it’ll be great. Apply for the money.”

So I did, and I got some funds, and flew to Boston, which just seemed like the big time to me, to be going to this conference, missing classes. I didn’t even have to drive. The conference was at the Copley Plaza, which is one of the most elegant, lovely hotels ever. And especially to a student, wow. There was all that snow. The worst of the storms were over but it was still piled up. I mean, just trying to cross the street, where the curb cuts are, you crawled up and over piles of snow. But I’d never been to Boston before so that was pretty impressive. Never been to a professional meeting before. Never stayed at a hotel like the Copley Plaza.

So my eyes were wide open. But Kiyo was right there, took care of me and, “Well, we have to go find some dinner, and let’s see who else wants to go.” So I met the people that were her friends, her colleagues, not just from the Midwest chapter. But she’d been around a long time and knew people. Some of those people I looked at at later meetings and I thought, “I met you in 1978 when I was a student just following behind Kiyo, and you were her friend and her colleague, so I met you.” And we went out to eat, and I just listened to them and took it all in. And they were such nice, collegial people that I’d run into them in the hallway, “Oh, hello, Pam, how’s it going? Do you like MLA?” And some of the big names, I’d read their publication in Notes or they’d written “the book,” and there they were. Just at the same conference I was at. Oh!

There were a lot of very meaty discussions. the things I was supposed to be learning in school, professional librarians were still discussing these things and dealing with them. One of the issues, and I’m pretty sure it was at that Boston meeting, was to not allow smoking during MLA meeting sessions. And I look back on it now and think, “Smoking in the meetings?” Another issue was meeting in states that had not ratified the ERA, Equal Rights Amendment. This just sounds like it’s out of the dark ages. Smoking in meetings, but these were big discussion topics.

There was a movie night. The movie was Desk Set. So we were invited for a fun evening. Come to Desk Set, and we’ll have popcorn and if you wanna come in your jammies, that’s fine. I thought, “Well, I am a student and pretty intimidated by this whole thing so I will not be in my jammies,” but I think it’s ok to say Suki Sommer came in her funny jammies, those little kid pajamas that have the feet. Big slippers she was carrying. A teddy bear or something. And she was so much fun anyway. But here’s this big name from New York Public and she’s coming in these kid pajamas and carrying a stuffed animal and I thought, “This is gonna be okay.”

So we ate our popcorn and watched Desk Set. And then at that time there was a closing banquet, usually with dancing afterward. Some of that continues now, but this was a formal banquet in a very formal ballroom and people really dressed up for it. I have no idea what the meal was, but I was really impressed. And then there was a little chamber ensemble for ballroom formal dancing. And there are some really good dancers in MLA. And just watching all that, these people who dress in funny pajamas and come to the movie and then they’re in elegant dress and doing ballroom dancing. This is a whole package deal, not just the sessions and learning a lot. This is an interesting group.

There was a tour of the city, so people were there to have fun, too. We hopped on buses and went to Harvard and MIT and the Christian Science mother house. Walked through that big globe (the Mapparium), and also got to see a little bit of the city. Somebody was always scouting out a restaurant, “Oh, let’s go try this. It’s really interesting.” So we went to Durgin-Park and things that typify the city. Now, that’s just what you do when you go to MLA. It’s “Okay, we’re gonna have some fun, and we’re gonna find good restaurants, and let’s get a little group, and let’s go see the city, and let’s go shopping. And buckle down and do our work, too.”

It was pretty heady for a student. And then, part of this grant was to go back and then tell your colleagues about it. So part of the class session, music bibliography, I gave a little report on the meeting and how impressed I was, and here’s some of the stuff I picked up. So I’d like to think maybe that helped some other people who hadn’t pursued it say, “Yeah, I’d better check this, I’d better at least join and I better go to some of the meetings.” So that was my first one.

MC: And obviously you continued. You mentioned that you contributed several chapters to the 1983 second edition of Basic Music Library.

PJ: Uh huh. And I think that was probably just a request in a newsletter. I was working in Kentucky at that time and when A Basic Music Library was finally published, I was then at UMass. But I was doing part of the professional activity. Community involvement, professional activity, how do you do your job, all those things that you’re evaluated on, but that I wanted to do. That’s what real music librarians do. And that’s what my colleagues were doing in their own areas of librarianship or other subject specialties. Worked with the editor and, what chapters did I have some background in, and could I actually draw on some expertise, and it pays to work on what you know.

I worked on that. And then when it was published, we were now into 1983 so I was at Massachusetts. Then the new kid looked good because [I had] contributed chapters to this thing published by ALA. I kind of got credit in both institutions, and that didn’t hurt. Yeah, it was a lot simpler then. I look at what we’ve gone through now to get the latest Basic Music Library. Oy. It was a lot simpler at that time. But it wasn’t the massive project that it is now either.

MC: Is there anything else that you want to have covered that we have not discussed yet?

PJ: I landed in a very good profession with good people. I hear people, especially not in the academic world, but some in academic, too, who are surprised by the strength of MLA and music librarians, what a tight group we are, how well we know each other. Our materials have very specific needs when we talk about electronic systems, whether it’s ILS, an integrated library system, or data[base]. And we’re usually the first to say, “But it’s not gonna work for uniform titles,” or “Well, we have to designate the material because you can’t just search for this composer and title if you can’t also indicate you’re looking for a score or recording.” And we’re the ones who are speaking up.

And I think we were one of the first, if not the first, special user group that was an outgrowth of OCLC. MOUG, The Music OCLC Users Group. And I think we were a model of what special interest people look for in a user group, and form a user group, and what they demand from their utilities and from their services. And part of that is because we know each other, because MLA is so tight and longstanding. I don’t know that many other fields that well, but I can’t think of anything that has the strength and longstanding commitment that MLA does.

And if you’re a subgroup of ALA, that’s a little different than being your own group and controlling your own destiny to some degree. With an outstanding journal and newsletters. And then we were one of the first, I think, to really develop a listerv, MLA-L, so that we could talk to each other more easily. And have directories so that we could call for help. Before we had electronics, you’d get on the phone and, “Well, I know that person at BU. I just need the phone number,” ‘cause there was no web. So, to find that and call and get some help.

And I think that just put me in a circle of good people, qualified people, passionate people about music and about libraries. And we’re a helping profession. We’re a service profession. And overall, that’s been my experience. People want to help. They want to help their students, they want to help their faculty, they want to help their community, and they want to help their colleagues. So, I did well. I landed in a good profession and in good places.

Submitted by Marci Cohen

_____________________________________

NEMLA Officers

Publication Information

New England Quarter Notes is published quarterly in September, December, March/April and June/July.

Back issues may be accessed from:

http://nemla.musiclibraryassoc.org/resources/newsletters/

Address all correspondence concerning editorial matters to:

Jennifer Hadley

jthom at wesleyan.edu

Inquiries concerning subscription, membership and change of address should be directed to:

Carol Lubkowski

clubkows at wellesley.edu

Membership year runs July 1st to June 30th.

Regular Personal Membership:$12.00

Student and Retired Membership:$6.00

Institutional Membership$16.00

Return to the New England Music Library Association home page.